Chris Hedges Report: Roots of Mideast Conflict

“It took the weight of the British Empire to turn the Zionist dream … into an agenda.” Historian and author Eugene Rogan on the consequences of the fall of the Ottoman Empire.

Modern borders represent mere lines in the sand when understanding the deep history behind the forces that drew them. In the contemporary Middle East, nations such as Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Egypt and most notably Palestine, cannot be fully understood without delving into the region’s intricate past — especially the pivotal role of the Ottoman Empire’s influence.

Eugene Rogan, the professor of Modern Middle Eastern History at the University of Oxford, joins host Chris Hedges to discuss his book, The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East, and explain how the modern geopolitical makeup of the region came to be.

While not the sole source of all conflict in the modern Middle East, studying the Ottoman Empire is essential for understanding both the region and the European powers that dominated during that era. World War I, in particular, marked a pivotal moment in the formation of modern nation-states. Britain, Russia and France emerged as key beneficiaries of the early 20th-century battles that reshaped global power dynamics.

Rogan provides an in-depth analysis of the complex relationships among monarchs, religious leaders, ambassadors and consuls, highlighting their crucial roles in shaping the region’s historical developments. His detailed and thorough examination provides a clear picture of how the region evolved as a result of the decline of the Ottoman Empire.

Rogan tells Hedges,

“Britain had maintained that the preservation of the Ottoman Empire was in the best interest of the British Empire, that it was a buffer state that bottled up Russia, kept it out of the Mediterranean world, and that, were this Ottoman State to collapse, all that geo-strategic territory in the Mediterranean world would soon become the stuff of European rivalries that could lead to the next major European war.”

On the question of Palestine, Rogan notes,

“Protestants in Britain, Catholics in France, Orthodox in Russia, all wanted a claim to the holy cities and the holy places of Palestine, and so Palestine was painted a kind of brown and internationalized.”

Rogan delves into the Zionist project, tracing its origins through collaboration with the British Empire and examining its evolving connection with the United States. He highlights the growing involvement of the U.S. in the region, which it thrusted itself into at the close of the 20th century and the dawn of the 21st.

Host: Chris Hedges

Producer: Max Jones

Intro: Diego Ramos

Crew: Diego Ramos, Sofia Menemenlis and Thomas Hedges

Transcript: Diego Ramos

Transcript

Chris Hedges: Welcome to The Chris Hedges Report. “The past is never dead,” William Faulkner writes in his novel Requiem for a Nun.

“It’s not even past. All of us labor in webs spun long before we were born, webs of heredity and environment, of desire and consequence, of history and eternity.”

Perhaps nowhere, historically, is this truer than in the Middle East. The fall of the Ottoman Empire — which for six centuries stood as the greatest Islamic empire in the world — in the wake of World War I saw the victorious imperial powers, especially Britain and France, carve up the Middle East into protectorates, spheres of influence and colonies.

The imperial powers created new countries with borders drawn by diplomats in the Quai d’Orsay and the British Foreign Office who had little understanding of the often autonomous and at times antagonistic communities they were attempting to herd into new countries.

They sponsored the colonization by Zionist settlers from Europe in the land of Palestine, setting off a conflict that continues with savage intensity today in the occupied Gaza and the West Bank.

They propped up autocratic dictators and monarchs – their descendants still ruling countries such as Saudi Arabia and Jordan — to do their bidding, crushing the aspirations of democratic independence movements.

They flooded, and continue to flood, the region with weapons to pit ethnic and religious factions against each other in the great imperial game that often revolved, and still revolves, around control of Middle Eastern oil.

The heavy-handed intervention in the Middle East, often based on false assumptions and a gross misreading of the political, cultural, religious and social realities, later exacerbated by the disastrous interventions by the United States, have led to over a century of warfare, strife and immense suffering of millions.

It is impossible to grasp the conflicts of today in the Middle East if we do not examine the causes and roots. There are three books that are vital to this understanding, David Fromkin’s A Peace to End All Peace: Creating the Modern Middle East 1914-1922; Robert Fisk’s The Great War for Civilization; and Eugene Rogan’s The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East.

We speak today with Eugene Rogan, the professor of modern Middle Eastern history at the University of Oxford about his book The Fall of the Ottomans and the creation of the modern Middle East.

Eugene Rogan: Well, first off, Chris, thank you so much for having me on, and it’s a real pleasure getting to have a little time to talk over the book with you. And, you know, as you rightly point out, it’s a book that had kind of family roots to it. It was a moment of exploration, having spent my career studying the Middle East and to better understand the Middle East of the 20th century, I was drawn into studying the Ottoman Empire, because all the origins of the modern Middle East can be traced back to the previous state that had ruled this area.

So to answer your question, you know, the Ottomans first make their entry into the Arab world in 1516 and 1517, when they turf out the then ruling Mamluk Empire, based in Cairo. They had an empire that spanned all of Egypt, greater Syria and the Hejaz, Red Sea province of the Arabian Peninsula. And they were able to, you know, the Ottomans were able to draw on gunpowder technology to affect a total decimation of Mamluk ranks.

Mamluk’s knights in the old fashion, you know, they were trained in swordsmanship and in horsemanship, and they thought that real men fought like chivalric knights, and they found themselves up against real men with guns, and men with guns won.

And that was to take the Middle East down the road of being part of what was then the largest, most successful Islamic empire in the world, and for a Europe or America that’s used to thinking of the West as dominant, I assure you that that Ottoman Empire was the most terrifying state in the whole of the Mediterranean basin, and was to remain so right through until the 18th century.

Map of Ottoman Empire’s largest borders in 1590, before the long Turkish war. Dark green is directly administered; light green represents vassal states. (Siksok, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Their last drive on a European capital would be in the 1680s when they laid their last siege to Vienna. So it’s just a corrective, you know, before we write this Ottoman Empire off and assume that it was slated to lose in the First World War, this was one very powerful empire that spanned three continents, and, you know, was basically the scourge of Europe right up until the 18th century. Chris, I assume you’d like shorter answers, rather than for me to go on with, great long speeches.

Chris Hedges: No, I’d rather that you go on. There’s no time constraint here.

Eugene Rogan: All right, very good.

Chris Hedges: So they get up to the gates of Vienna, but then they’re as you write, they’re rolled back. This is all before World War I. So the empire begins a kind of slow disintegration on the eve of the war, perhaps you can just explain what happened.

Eugene Rogan: Well, basically what happens is Europe takes off. I mean, the Ottoman Empire was a perfectly strong and viable empire in its own right, but it found its European neighbors taking off with two major developments. One is the Enlightenment, and just the new ideas that spill into politics and how to organize a country better, more efficiently, better at raising tax money, and how to develop cities and whatnot. And then the other, of course, is going to be the Industrial Revolution. And those two developments, coming in the end of the 18th century, are going to impel Europe into a high gear that leaves the Ottoman Empire far behind.

And in the 19th century, the Ottomans become increasingly aware that every time they go to the battlefield with their European neighbors, they’re losing and they’re losing territory. It starts with losing territory in the Crimea to Russia, they begin to lose territories to the Habsburgs in Vienna and the Ottomans begin to ask, what is it going to take for us to revitalize this one dominant empire?

And in the 19th century, they settled on a reform program. It spans the years 1839 to 1876, where they just try to affect a root and branch reform of the governments and the economy of the Ottoman Empire, so that they might be able to take advantage of the new ideas of the Enlightenment, the new technologies of industrial Europe, and re-emerge as a player and as a power.

But by the time they reach the 20th century, the challenges the Ottomans are facing are almost insurmountable. The gulf between where they stand and where the European neighbors stood was almost unbridgeable. And you know, if you’re trying to buy the technology for your own development from your adversaries, it’s a game you’ll never win.

You’ll never overtake Britain and France by trying to buy their own technologies or ideas, they’ll always keep you one step behind. And I think that’s where the Ottomans found themselves in the beginning of the 20th century, as they were sort of coming into their first real conflict of total war with the most powerful states of Europe in World War I.

Chris Hedges: And so on the eve of World War I, there are all sorts of independence movements in the Balkans, the Ottomans are pushed back. Maybe you can explain a little bit about how that happened, and they ultimately built an alliance with Germany. One of the interesting conflicts, of course, within the British government, was that it had been a cornerstone of British policy to essentially leave the Ottoman Empire intact.

This is, you know, that battle is lost by the end of World War I, but so just get us up to the eve of the war.

Eugene Rogan: So among the ideas to come out of the European Enlightenment, nationalism was to be one of those contagious. And for a multinational, multi-ethnic empire like the Ottomans, it was really an existential threat. Nowhere was that more apparent than in the Balkans.

We’re starting with Greece’s uprising in the 1820s. You’ll have a century between 1820s Greece right up until Albania declares its bid for independence in 1913, where virtually every Christian majority territory of the Balkan Peninsula seeks its independence from the Ottoman Empire.

All those are territories the Ottomans had conquered from the Byzantine Empire, going back to the 14th and 15th centuries and by the 20th century, you know, on the eve of war, they pretty much lost every last bit of their European territories except a little bit of Thrace, which is that little piece of Europe in modern Turkey, which Istanbul straddles.

And, you know, in 1908 the reformists come back to power in a revolution which overturns Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who had, in many ways, tried to put the power right back into the Sultanate and take it away from government, the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 reverses that.

It’s a moment where I think many in the Ottoman Empire believed there would be a process of renewal, particularly binding the Muslims of the Empire, recognizing the Balkans were a lost cause. But in the course of the first years after that revolution, the Ottomans were just hammered by a succession of wars.

The Italians make a bid for Libya. They want their own patch of imperium in North Africa and invade the territory, to squeeze the Ottomans to finally give up on Libya, the Italians lean on their relations in Montenegro to rise in what becomes the First Balkan War.

The Ottomans are thrashed in the First Balkan War of 1912 and then this is when they really lose most of their remaining Macedonian and Albanian and Thracian territories in the Balkans.

And then there’s a second Balkan War in 1913 where the Ottomans take advantage of the Balkan states like Bulgaria and Greece and Serbia falling out among themselves over the division of loot, like so many thieves, and are able to reclaim the city of Edirne, and that little stretch of Thrace, as I said before, is still part of modern Turkey. So the Ottomans are just rocked.

By 1914, their economy was, you know, exhausted. They took $100 million loan from France to try and rebuild their economy. Their army was broken. They reached out to Prussia to help them rebuild the Ottoman army. And they needed to reach naval parity with their great adversary, Greece, and they reached out to the British for help with rebuilding their navy. They even commissioned two state of the art dreadnoughts from the Harland shipyards in Northern Ireland.

So the Ottomans, by the time they reach 1914, have had enough with revolution and war. They’re counting on a period of calm and peace so they can try and rebuild their empire, their military, their navy, to withstand the challenges of the 20th century. But they just weren’t left much of a breathing period from that sort of autumn and spring of 1914 to the guns of summer in August of 1914.

Chris Hedges: And just a little footnote, Trotsky covered the Balkan War. His book’s actually very good, and then used whatever three or four months there to, after the Bolshevik Revolution, make him minister of war. So one of the things about the Ottoman Empire is that it, and you make this point in your book about you know, once the war begins, is the diversity of nationalities, ethnicities, not just Shia and Sunni, but Christian, Yazidi, Kurdish, that incorporated, they played such a major role after the war when Sykes–Picot essentially when they redrew the maps and created these modern Middle States.

But you also note that the battles in the Middle Eastern battlefields, you say, were often the most international of the war. Australians, New Zealanders, every ethnicity in South Asia, North African, Senegalese and Sudanese made common cause with French, English, Welsh, Scottish, Irish soldiers against Turkish, Arab, Kurdish, Armenian, Circassian and their German and Austrian allies.

I mean, that was one aspect of the war, which I didn’t know. The other was a point you make, for instance, on the I think it’s on the Gallipoli campaign, where you talked about how you could be on the Western Front, it could be dormant for months.

That wasn’t true in places like Gallipoli. So talk a little bit about, and I think that when we see the creation of the modern Middle East, especially when the imperial powers went in, in order for their own ends, they started pitting these groups, ethnicities — and that’s my dog there, sorry — that these ethnicities, one against the other, but talk about that international aspect.

Eugene Rogan: Oh, it’s one of the most interesting things about studying the First World War from the perspective of the Middle East. I argue that it’s really the Middle East that turned a European conflict into a world war. If you look to what went on in both the Pacific theater and in the African theater of the war, it really had nowhere near the depth of gravity of the First World War in the Middle East.

And I think the expression I use in the book as I describe these battlefields with all these different nations and nationalities as a virtual sort of Tower of Babel, and that just meant that some of those battlefields were absolute chaos, and this gives rise to some funny anecdotes. You know, one of my favorites from Gallipoli was very early after the Allied landing in the beaches of Gallipoli, which went off very badly.

They found themselves coming up against deeply entrenched Ottoman forces who were waiting for them and mowed them down with machine gun fire, or else they found themselves trying to scale cliffs that their maps just hadn’t prepared them for. So they arrived often separated where soldiers and commanders were not together. Soldiers without commanders often really don’t know how to take initiative in the battlefield, and in one case, a group of brown men come up to British commanders and asked to, you know, meet their commanding officers.

And so the lieutenants take them to the captains, and the captains take them to the major. And these guys maintain that they’re Indian soldiers looking for their colonel, and instead, they wind up capturing like five or six British officers, because those were Turks in disguise pretending to be Indian soldiers, taking advantage of the credulity of these confused Tower of Babel soldiers.

So yeah, it’s an element of the First World War that, you know, you think about the battlefields of the Somme, you know, Germans and Frenchmen and Englishmen fighting against white men. That was not the Middle East. The Middle East was truly a battlefield of diversity.

Chris Hedges: Let’s talk a little bit about the Ottomans were kind of agnostic as to who their allies would be. They ended up, of course, aligned with Germany, almost by default. The Germans also sent quite a bit of money so the Ottomans could build their forces. But I think, as you said, the main concern was the preservation of the empire they had left. They didn’t, it doesn’t appear that they really cared at that point, which of the warring powers would ensure that. Is that correct?

Eugene Rogan: Well, I mean, if anything, there was a tendency to see Germany as a more reliable ally than either Britain or France. You’re dead right. On the outbreak of war, the Ottomans were willing to cut a deal with virtually any great power to enter into a defensive alliance and protect the territory from the fallout of war. They knew that in February of 1914, Russia’s government had passed a policy that in the cloud of war or the fog of war, Russia would seek to take the city of Constantinople, the Ottoman capital, under Russian rule, as well as the vital straits between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean.

These are the Bosphorus, the Sea of Marmara, and the Dardanelles themselves. This is a really important sea corridor for all of Russia’s exports, from Ukraine and Russia, to the Mediterranean world. And of course, you know, the coming war, it was going to be an important line of communications, were it open, between the Entente powers. So Russia had geo-strategic as well as cultural reasons for wanting to try and seize these Ottoman territories. And they wanted to make this bid because they’d seen how in two Balkan Wars, the Ottomans have proved quite weak.

And I think Russia was worried that maybe the Greeks would get to Constantinople first, as protectors of the Eastern Orthodox Church, Russia really wanted Constantinople, the Hagia Sophia Basilica, and all of the Byzantine treasures to come to their credit.

So, you know, with these drivers, the Ottomans were very concerned to keep their longest standing rival, Russia, at arms length. And if they could have carved a deal with France, who, as I just said, had given the Ottomans, in the spring of 1914, a $100 million loan. Or the British, who, as I just said underwrote a mission to help rebuild the Ottoman Navy, and had commissioned, you know, dreadnoughts for the Ottoman navy.

If they could have gotten the British or the French to sign a deal that would protect their lands against the Russians, they would have done it. But of course, there’s no way that the British or French were going to guarantee Ottoman territory against their ally, Russia.

Germany, by contrast, had no territorial ambitions in the Ottoman Empire. They never colonized an inch of Ottoman land. The French had, the British had, the Russians had. And so, they were militarily strong. They were technologically strong, very ahead of most of European powers. And if you were taking a bet, if you were a betting man, Chris, in the opening days of summer war of 1914 you might well have thought that Germany was going to win that war.

I think the Ottomans made a bid to go with Germany, in the hope that their bet would pay off and that they’d be among the victors being able to reclaim lands that they’d lost to the Balkan neighbors, or to Russia, or islands to Greece, having been on the winning side of the First World War in siding with Germany.

But the question is, what did the Germans get out of making an alliance with a country that most of Europe really did see as the sick man of Europe? And I guess that’s the harder one to explain.

Chris Hedges: Well, the British certainly furthered that process by seizing the dreadnoughts.

Eugene Rogan: Which set off a firecracker of fury among Ottomans. They felt absolutely cheated. Germany took advantage of that, had two of their own warships fleeing across the Mediterranean after bombarding the coastline of Algeria, with the British in hot pursuit, the Breslau and the Goeben enter into Turkish waters, where they’re re-flagged as Turkish vessels, and then are sent into duty in the Black Sea. And will, you know, draw the Ottoman Empire into the war.

But what was in it for Germany? We know they didn’t want Ottoman territory. They also had a very good sense of Ottoman military weakness after the two Balkan Wars. After all, it was their German, Liman von Sanders, their general, Liman von Sanders, who was the head of the German military mission to rebuild the Ottoman army. He knew where the problems lay. But here’s the trick.

A German Orientalist had persuaded the kaiser that the sultan, in his role as caliph over Sunni Muslims, could turn this war, not just into a world war, but into a Jihad. And that in this way, he could play on the religious sensibilities of Sunni Muslims in India, in the Caucasus under Russian rule, and in French North and West Africa, to create a global jihad that would weaken the Entente powers in their colonies.

And that was to become the kind of Ottoman secret weapon that was what drew the Germans into an alliance with the Ottomans.

They knew the Ottomans would drain them of gold and of guns and of artillery, but they thought that if they could get the Ottomans to break the stalemate of the trench warfare by weakening the Entente powers through their colonial possessions, through their colonial Muslims, then this would justify going into an alliance with the Ottoman Empire.

Chris Hedges: And initially the Ottoman forces, we mentioned Gallipoli, you can explain, but not just Gallipoli at Kut and and they do have some very capable German officers. They have, I think when they attacked the Sinai, they had Austrian artillery, if I remember from your book. They have, initially, some pretty spectacular successes, though the British force at Kut under Townsend has completely wiped out.

And by the end, I think the British are tied down with one and a half million troops, is that right? So it is initially the Ottomans that make huge advances.

Eugene Rogan: Yeah. I mean, I think the thing to remark is that, though written off by their European neighbors after so many military defeats, the Ottomans actually proved to be very tenacious in the First World War.

You know, they’re going to last until within 11 days of Germany withdrawing from the war. They outlast Bulgaria. So the Ottomans, in the event, proved to be very tenacious in defending their land against the British, against the French. And so you’ve pointed to their victories. They drive the British and French out of the Dardanelles in the Battle of Gallipoli.

They drive the British back in from Baghdad and then besiege Kut Al Amara, whereas you say, General Townsend is forced to make the biggest surrender, wait for it American listeners, since the Battle of Yorktown, when 12-to-13,000 British officers and men were forced to surrender, total surrender to the Ottoman forces. I mean, practically a gift to the Ottoman Empire.

And then in Palestine, the Ottomans will beat the British back in two successive battles of Gaza. Gaza, of course, of tortured memory in 2024, where the British unleashed hell from warships offshore.

They deployed tanks, the only time tanks were deployed in the Middle Eastern Front, and they even used gas artillery shells to try and drive the Ottomans out of Gaza, all to no effect. The Ottomans drove the British back twice, with high British casualties in both instances.

So the Ottomans demonstrated their mettle and their willingness to defend their territory. And of course, the other thing to say is, in the First World War, you learned that defenders were usually in a stronger position than attackers. If you wanted to attack, whether it was in the Western Front in the trenches or the Ottoman front, you had to actually expose yourself and run across ground, and that’s where the machines of industrial warfare, the machine gun and artillery, just decimated troops.

So one explanation for the Ottomans was they were defending their own land, and they were tenacious. But the other is, defenders usually fared better in the First World War by not exposing themselves to the high kill rate of artillery and machine gun fire. But anyway, it was to prove, in the event, a very tenacious Ottoman Empire that was Germany’s best ally in every respect, far less of a drain than Austria was in the event.

Chris Hedges: Let’s talk a little bit about especially the British response, because this begins to lay the foundations for the modern Middle East. The British had a belief in the power of worldwide Jewery. They actually were worried that the Germans would offer a Zionist state and there was a fictitious vision of worldwide Jewery, of course, but they create the so called Arab Revolt, but this and then the Hejaz, but they have to begin to make promises that affect the shape of the Middle East following the war.

So explain the British response and explain the promises they had to make.

Eugene Rogan: Yeah, great question, Chris and you know, in writing this book, there are lots of levels to the Ottoman First World War. And one is just about battlefields. I felt like it was important to bring the stories of those battles to British and American readers who just weren’t familiar with those battlefields.

And then another level is going to be that of the civilian suffering and the crimes against humanity, such as the Armenian genocide.

And then running right through the story is the wartime partition diplomacy that’s being conducted by the three Entente powers, Russia, Britain and France.

And I think one thing I bring to this book that’s going to be new to your listeners, new to my readers, is the Constantinople Agreement, which is the first of the wartime partition agreements. It was cut between March and April 1914, just on the eve of the opening of the Gallipoli campaign.

And anticipating a quick collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Russia makes its bid. It comes out in the open to its allies, and says, when we beat the Ottomans, we, Russia, want Constantinople and the straits to come to the Russian Empire. We also want a little more territory in eastern Turkey, in the Anatolian regions of the Caucasus.

So the British and the French go, okay, but that’s a really big war prize. France says, in return, we want all of Cilicia and all of Syria.

Now to listeners, those Roman toponyms aren’t going to mean a great deal, but Cilicia is the area around Tarsus and Adana in southeastern Turkey. And Syria, we know is Syria. When you think of greater Syria, not just the modern state of Syria, but everything from the Taurus Mountains down to roughly the Sinai Peninsula that would include Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Israel, Palestine. Syria meant sort of that, not particularly well defined.

But the interesting thing about the Constantinople Agreement of March, April 1915 is that at that stage, Britain had absolutely no territorial interest in the Ottoman Empire. They said as much as they reserved the right, without prejudice, to claim equal strategic territory as of when they worked out what would be the interest of their empire.

But as you mentioned before, Chris, until this point, Britain had maintained that the preservation of the Ottoman Empire was in the best interest of the British Empire, that it was a buffer state that bottled up Russia, kept it out of the Mediterranean world, and that were this Ottoman State to collapse, all that geo-strategic territory in the Mediterranean world would soon become the stuff of European rivalries that could lead to the next major European war.

The British were constantly saying, though we are allies with Russia and France today, we could imagine that we would be in rivalry and indeed in conflict with them in the future. And so this is what drives the British when they recognize that now at war with the Ottoman Empire, and they’re agreeing to Russian and French demands to carve that territory up when they beat the Ottomans, that they’re going to need to sit down and work out what would be the interest of their empire.

And they do the typically British thing, reader of [inaudible] and this will be familiar to you, they convene a committee of mandarins and people from the foreign office to just sit down with the maps and work out what in Ottoman lands would complement the British Empire.

They wind up deciding on Mesopotamia because it caps off that sort of British sea of the Persian Gulf. By this point, from Kuwait right to Oman, all the Arab shores of the Persian Gulf were under treaty relations, binding them to a kind of colonial situation under British rule. And so they saw Mesopotamia as the head of the Gulf, fitting British imperial interest, advancing the interests of the British Imperium in India and that will become the land that they demand further on.

But in that first instance, in March, April, 1915 when asked, okay, what bit of the Ottoman Empire do you, Great Britain, wish to claim? They had to refer to a committee decision. It wouldn’t be for a year before they’d finally get around to deciding exactly what they wanted.

Chris Hedges: Let’s talk about the Balfour Declaration. I mean, it becomes a key kind of document in terms of the creation of the modern Middle East and what was the impetus behind it?

Eugene Rogan: If I could, before I get to Balfour, I’m going to mention two other household names. One is the letters exchanged between Sharif Hussein of Mecca and Sir Henry McMahon, the high commission of Egypt. And that was when the British had lost in Gallipoli and were already on the retreat in Iraq, they decided that rather than draw more troops into the Middle Eastern Front, remember, Britain was committed to maximizing their troop presence on the Western Front in France and in Belgium, where they thought the Great War would be won or lost, so they didn’t want to divert any troops to Middle Eastern battlefields. T

hey hoped that they might be able to stimulate the Arab world to rise up against the Ottoman world.

If you like, it’s the flip side of the coin of the jihad idea that the Germans were so enthralled with, where you could try and drive not global Muslims against the enemy, but in this way, try and create a kind of broader Arab identity politics, and turn that against the Ottomans, and create an internal front against the Ottoman Empire.

To do that, Britain promises Sharif Hussein of Mecca, the Sharif of Mecca was the highest ranking Arab religious authority in the Ottoman Empire, he promised him an Arab kingdom.

And he, this is Sir Henry McMahon, the High Commissioner of Egypt, tried to carve out what he understood Britain had already given France by separating out those districts to the west of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo, roughly Mount Lebanon and the Syria coastline, cuts them out of what they promised for the Arab kingdom, saying it’s not strictly Arab.

And they also, at this point, claim a kind of short term interest in Mesopotamia, the provinces of Baghdad and Basra. And they get Sharif Hussein to accept those opt outs.

But basically, they’ve now committed to creating an Arab kingdom on all of the Arabian Peninsula and most of Syria and Iraq. Then, they realized they got to go back and make sure they know exactly what France wanted out of Syria and Cilicia, already promised in the Constantinople Agreement.

So think of this wartime partition diplomacy as this kind of ongoing process trying to negotiate the ultimate carve up of the Ottoman Empire. This gives rise to the meeting between French and British diplomats that we know today as Sykes-Picot, and in that, Sir Mark Sykes, who was an amateur Middle East expert, who was Lord Kitchener’s preferred man on the dossier, is put in charge of negotiating with the French former Consul to Beirut, a man by the name of Georges Picot, and the two of them sit down with a map and try and carve up spheres of influence and areas of direct rule and that’s Sykes-Picot.

But, critically, Russia, France and Britain could not agree on who would get Palestine with its holy places, all three with their kind of state churches; Protestants in Britain, Catholics in France, Orthodox in Russia, all wanted a claim to the holy cities and the holy places of Palestine, and so Palestine was painted a kind of brown and internationalized.

And I think that’s the critical thing that Britain was hoping to overturn when it began to court the favor of the Zionist movement and put the weight of the British Empire behind what had, until that point, been the least realistic romantic nationalist movement in modern European history.

Why was Zionism so unrealistic? Because there was neither a territory on which the Jewish people represented a majority, and indeed not a demography, because the Jewish people were in diaspora across Eastern and Western Europe, North America, South America. So the idea that you were going to try and create a Jewish national movement with a land mass that they weren’t even a presence in a very, very small 2-3 percent of Palestine was Jewish before 1914.

It took the weight of the British Empire to turn the Zionist dream from being a dream into an agenda that actually could be realized. What was in it for Britain?

They could use the great idea of solving Europe’s Jewish question, this chestnut that had bred anti-Semitisms of many different stripes over the 18th and 19th century, and at the same time, win the support of the Jewish International, this anti-Semitic trope that was given a great deal of credence.

And frankly, the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann, was very happy to encourage European and British statesmen in particular, to imagine that Jewish financial and political interests would meet in back alleys to plot the fate of the world.

And if this thinking led the British to support the idea of creating a Jewish homeland in Palestine, then Weizmann was very pleased to promise that he would use his best influence over the recent revolution in Russia, that it brought the new government to power, that maybe this could lead to revitalization of the Russian war effort before the Bolshevik seizure, and indeed, get that reluctant America to commit itself more fully.

Remember that America was isolationist, wanted no part in the First World War, took until April of 1917 to even declare war on Germany. And at that point, had armed forces that, if you threw the Coast Guard in, didn’t surpass 100,000 men. Needed to go to conscription, needed to engender national will and Chaim Weizmann was there to say, you will get the support of American Jewry, with all their financial support, to try and make this happen.

Weizmann in 1900. (Bain News Service, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Chris Hedges: There was even this fantasy that the Bolsheviks were essentially a Jewish-driven entity.

Eugene Rogan: So I don’t think Weizmann was in it for anything other than advancing the goals of the Zionist movement. That was his brief. But if he were to, you know, turn around and let’s be honest, the statesmen of Britain at the time were themselves notorious anti-Semites.

If you look at Lloyd George and the people in his cabinet, even Arthur James Balfour, I can find you some very juicy anti-Semitic things these men said. Their turnaround had more to do with the geo-strategy of Britain’s wartime partition diplomacy and their recognitions of there were now territories in Ottoman lands that were going to be vital to Britain’s Empire, and Palestine really gained a new importance to the British when they saw that having a hostile power in Palestine could always threaten the Suez Canal.

The Ottomans had done it twice in the course of the war. And I think the difficulty the British had in prosecuting a campaign in the Sinai and then on the southern gates of Palestine, with the two lost battles of Gaza before the final breakthrough at Be’er-Sheva, told the British that you could not leave the Palestine at risk of being in hostile hands, or you wouldn’t be able to guarantee the security of that vital strategic artery of empire, the Suez Canal.

So that’s what changes for the British, and that’s where the partnership with the Zionist movement comes from. And from there we get probably the most enduring commitment of the partition, a partition diplomacy in World War I, the Balfour Declaration of November 1917.

Balfour Declaration as published in The Times, Nov. 9, 1917. (The Times of London, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Chris Hedges: And I’ll let you explain what that is. But we should be clear that the Prime Minister Lloyd George becomes quite an imperialist. He came out of the Socialist Labour Movement, but he is very covetous of land, which flies in the face of earlier British policy within the Ottoman Empire. But just briefly explain Balfour, and then I do want to talk, because you write about it, about the genocide of the Armenians.

Eugene Rogan: I mean, the Balfour Declaration is a household name. It was Britain’s promise to look on favor with the creation of a Jewish national home in Palestine, without prejudice either to the rights of Jews living outside Palestine. So this was not to be a free for all, for anti-Semites who wanted to drive Jews out of Britain or America saying you got your own homeland go.

But at the same time, it was not to prejudice the civil or religious rights of the non Jewish people of Palestine. Now, Palestinians, to this day, will take offense at the fact that at no point does the Balfour Declaration mention Palestine or Palestinians as a separate national entity. But I frequently remind my Palestinian colleagues that neither does it actually call for the creation of a Jewish state.

It uses the deliberately ambiguous terminology of a national home, something with no precedent in international law or the history of diplomacy, even someone like archimperialist Curzon, Lord Curzon questions what it is that Britain’s committing to, not knowing what the deuce a national home was. And Churchill and those around him said precisely, well done. That was the way they wanted to keep it, vague, get what they needed out of the deal.

But basically, Britain was in it for the British Empire. They were not pro-Zionist, they were not particularly pro-Arab. They were anti-nationalist in any guise. So they never promised the Zionist movement a Jewish state. That was very far from the thinking of the British.

They saw Palestine as geo-strategic territory for upholding their empire, and Lloyd George, the moment he becomes prime minister, has the same duties of preserving the interests of the Empire as his most conservative predecessors, because Britain’s place in the world, particularly if it was to come out of the First World War, that death struggle for existence, victorious, it would be the empire that was going to allow Britain to re-establish its place as a power of the world. So they were all committed imperialists.

Our mistake is to think that they were carried away by romantic ideas about Zionism, or indeed Palestinian-Arab rights to nationhood, that simply wasn’t in the calculus of the British government with its imperialist imperatives right through the 1920s and 30s.

Chris Hedges: So let’s talk about the Armenians. Again, they get caught up in this kind of great game. They make armed assaults in an effort, you write, to essentially entice or provoke European intervention, it backfires completely, and we get the first genocide of the 20th century.

Eugene Rogan: The Armenian tragedy does have deep roots. And in the book, I have to take us back to the 1870s when Russia first uses the Armenian people as a sort of cat’s paw into intervening in Ottoman affairs.

And they call for a kind of Armenian reform project in the Treaty of Berlin, which would give Armenians autonomy in, really, Turkish heartland and eastern Anatolia and the Ottomans, at that Treaty of Berlin, coming after the Ottomans lost a terrible war to Russia, were in a weakened position, needed European good favor, and they just go with it, saying, yeah, yeah, yeah, but they put it off over the next horizon, and in the interim between 1878 and the end of the 19th century, the Armenians, themselves, begin to buy into the ideas of nationalism.

And you have nationalist movements emerging in Europe or in Ottoman Anatolia, the Dashnaks, the Hunchak movements, some of which turn to armed violence to try and advance their cause.

And this is going to set off violent responses by the state of Sultan Abdul Hamid II that leads to some of the most horrendous massacres in the 1890s that was going to lead the sultan to be nicknamed the Red Sultan, or the Bloody Sultan, for the blood on his hands in both Bulgaria and in the Armenian territories of eastern Anatolia.

And again, you have in the overthrow of Sultan Abdul Hamid II in 1909, he tried to mount a counter revolution. It was put down by the Young Turks. And then, inexplicably, the coastal city of Adana erupts in sectarian violence, in which, again, thousands of Armenians are the target and are killed.

This goes entirely against the grain of the revolutionary moment, where many of the Armenian political movements had sided with the Young Turk revolutionaries, had stood for election in the Ottoman Parliament and were absolutely committed to the Young Turk Revolution.

So you have this period, I would say, from 1909 right up to the outbreak of the war, where Armenian loyalties are in the balance.

But when war is declared, and even before the Ottomans end of the war, they have general conscription. Armenians flock to these conscription centers in the towns and cities where they lived, like every other Ottoman citizen of the required age, whether you were a Christian, a Muslim or a Jew, you had to turn out for conscription, and the Armenians did so in great numbers.

But one of the first fronts to erupt into direct warfare in the Ottoman front was actually between the Ottomans and Russia in the Caucasus.

In the dreadful Battle of Sarikamish at the very end of December 1914 and early January 1915 and it was, if you like, one of the ruling triumvirate, Minister of War Enver Pasha’s bold gamble, rash gamble, to take his strongest army, the Third Army, and send them into what turned out to be four or five foot snow drifts without adequate clothing or food or shelter, and in which the Third Army, about 80-85 percent of the Third Army perished, not on the battlefield, but of exposure.

The problem was that was the same territory of the encounter between the Russians, who had occupied a large part of Ottoman Caucasian territory inhabited by Armenians.

So there are Armenians in the Russian army calling to their fellow Armenians in the Ottoman army to cross sides. And many Armenians do. They do so not just out of the appeal of the fellow Armenians in the Russian side, but because they become the target of suspicion by their Ottoman fellow soldiers.

And reading the diaries of Ottoman soldiers, I was able to capture this murderous turn that takes place in Ottoman ranks, where there would be accidents, where a gun would discharge in the general direction of a group of Armenians, and no one was ever punished for the Armenian soldiers killed by their Turkish fellow soldiers.

Chris Hedges: You write, three to five a day were being shot, Armenian soldiers, by accident.

Eugene Rogan: Yeah, which leaves the Armenians more and more responsive to calls from their brothers on the Russian front. But then, of course, the flight of tens and scores of Armenians across the frontier into Russia makes matters worse for those Armenians who stay behind and in the aftermath of the defeat at Sarikamish, where, as I said, only 15 to 20 percent of the Third Army returns back to their base.

The Ottomans never were able to re-establish their defensive lines in the Caucasus. This territory was now open to Russian forces, almost unprotected, and they’re a large part of the population, about 20 percent was Armenian.

And it’s at this point in March, April 1915 that the Young Turk regime begins to plan for measures to depopulate eastern Anatolia of its Armenians, but then measures designed to separate the men from the women. The men are immediately killed, and we have too many accounts by civilian survivors of this process for us to begin to question the veracity of the accounts.

And then only the elderly and the women and children would be grouped into columns to march from their villages in eastern Anatolia down to the Mediterranean coastline around Tarsus and Adana, and then from there, they would be sent through the Syrian desert, but under conditions in which very few people could survive, and this being territory, the Ottomans knew very well, you could only assume it was a policy of mass extermination by forced march through desert conditions with high exposure, no water, no food and the result was a genocide.

I mean, even the Ottomans, at the end of the war recognized what they then called, the term genocide hadn’t been coined yet, they spoke of massacres, and one of the triumvirs, Jamal Pasha, ruling the the Young Turk regime described the killing of 600,000.

So I mean even that point, the Ottomans were willing to recognize that their measures had claimed at least 600,000 the high count from some Armenian activists today seeking justice for the genocide will claim as many as 2-2.5 million. I think a lot of scholars are coming to a figure, based on demographic extrapolation, of somewhere between 900,000 and one and a quarter million.

I say a million as a rough figure. But we don’t really have a more precise figure, because we don’t really have the census numbers. There was never a head count of those who died, and we don’t really know how many people, particularly women, disappeared and were absorbed into Muslim households to live the rest of their lives raising Muslim children as loyal Turks.

A very celebrated book written by a Turkish lawyer named Fethiye Çetin, My Grandmother’s Story captures this experience of survivors of the genocide taken into Muslim households and who spent the rest of their lives raising Turkish families.

Chris Hedges: Although the Turks today strenuously deny that it was a genocide after the war, there was an investigation and a trial which provided extensive evidence for exactly what you said, these are actually one of the primary sources, are Turkish sources.

Eugene Rogan: Turkish court records, and it’s a really important source. But you have to remember, by the end of the war, the Young Turk regime that had governed the Ottoman Empire right through World War I had dragged them into the war, you know, guided them through some of their rashest decisions, at wars end, they fled.

And so there is, in a sense, a wish on the part of the successor government of the Ottoman Empire to wash their hands of responsibility for the crimes of the Young Turk. And they knew that the Armenian genocide was going to be at the top of the list, not least because the American ambassador in the Ottoman Empire was a man by the name of Henry Morgenthau. And Morgenthau’s reports were widely published in the American press.

The New York Times does literally scores of stories about the massacre of Armenians, and already it’s being described in the press at the time as one of the most atrocious crimes against humanity committed in the course of the First World War. That genocide hadn’t been coined yet, but crimes against humanity that expression was in circulation.

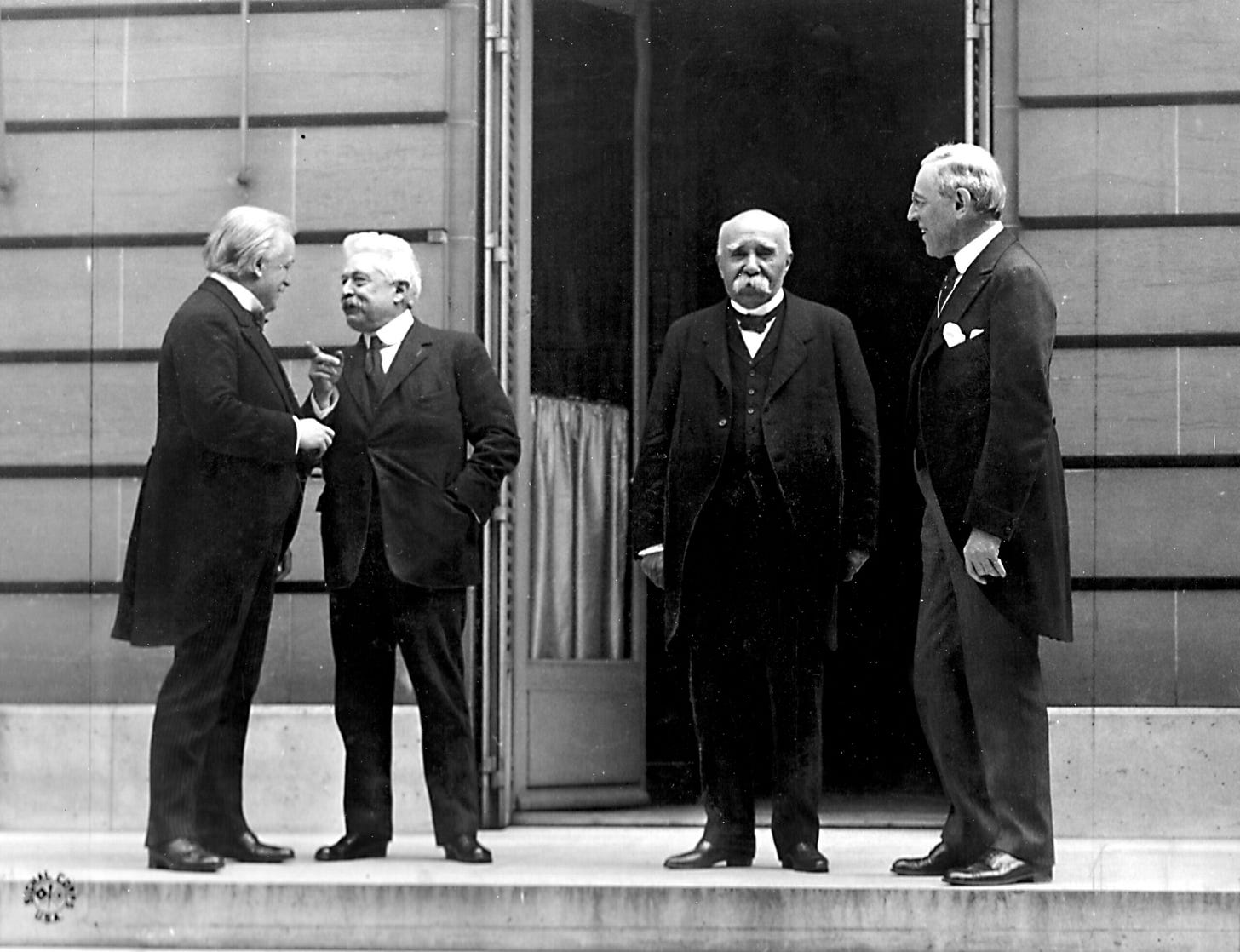

So the Ottomans were determined to address the issue of the Armenian massacres, as they were then called, knowing that they would be held accountable for this, and it was something they wanted to show the world that they were addressing seriously, that when the Ottomans went to Paris to negotiate the peace treaties, that they could try and negotiate a treaty that would preserve their Ottoman state within its current frontiers and not face the kind of draconian partition that they were certainly aware the Entente powers had been discussing right through the years of the war.

Council of Four at the WWI Paris peace conference, May 27, 1919: from left, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Italian Premier Vittorio Orlando, French Premier Georges Clemenceau, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson. (Edward N. Jackson, U.S. Signal Corps, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

So this is the background, and they do make many arrests. They try people in absentia. They condemn people to death in absentia, they even have some people who they hang for their crimes against the Armenians. But those records remain some of the most graphic accounts that we have.

And while you’re right, Chris, I mean the Ottoman, sorry, the Turkish government today continues to deny genocide, some of the best scholarship we have exposing the Young Turks crimes against humanity are coming from Turkish historians today. So, you know, there is a movement among scholars in Turkey to try and find a true historic narrative and some degree of justice for those crimes

Chris Hedges: Of that ruling triumphant, I think you write only Enver, the other two are assassinated, and only Enver survives. Let’s talk about, so you had two empires, or maybe we can count three, with the Russian Empire, but certainly Austro-Hungaria disintegrates in the wake of World War I, as does the Ottoman Empire, but they’re treated very differently.

There’s autonomy, you know, a kind of Wilsonian belief in self-determination for the states in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. That is not true in the Middle East and we’re really living with that legacy today. So explain what happened at the end of the war and why the essentially domination of most of the Middle East, from Egypt running all the way up through Lebanon and Syria and has essentially laid the groundwork for where we are today, including, of course, Palestine.

Eugene Rogan: Well, remember, we were talking before about the reluctance of the Americans to come into the First World War. And one of the things that President Wilson had to do to sell this idea was to cast America’s role as a kind of savior of a breakdown in world order that only the Americans really had the kind of moral vision to set right.

And the problems of the European order were obviously secret treaties, which meant that countries were being duplicitous with each other, double dealing, conniving, whatever. But also empire.

Wilson’s criticisms of empire were really harsh, and talking about how they would no longer be the trading of people like chattels, you know, lands and people being exchanged between powers, while the Asians and Africans had no say in their fate. And I think that certainly, you know, Wilson’s Presbyterianism would have inspired to some degree that thinking.

I also think that industrially strong United States was looking for markets beyond its shores and found empire as one of those barriers to entry that had frustrated, you know, automobile manufacturers or sewing machine makers.

So Wilson’s anti-imperialism had moral as well as practical demands, but he set in motion ideas about a new world order based on open treaties and diplomacy and anti-imperialism and all of that wartime partition diplomacy that Britain, France and Russia had been negotiating was precisely about trading lands and peoples as chattels.

So as Wilson comes to Paris to meet with the victorious powers in deciding the fate of the defeated powers, he’s holding to his 14 points, and he’s frowning on efforts to try and make a major carve up by Britain and France, in a sense, trying to demonstrate to their own citizens that the sacrifices of World War I would be redeemed by the kind of territorial gains for their empires.

And what they wind up doing is they wind up coming up with a compromise solution in which the territories of the Ottoman Empire would be deemed to be newly emerging states that didn’t have the institutions of the experience to run themselves to the standard of a modern state today in the 20th century.

And so rather than colonies, they were to be mandates entrusted to experienced countries like Britain or France, who would be answerable to this new international organization called the League of Nations, the precursor to the United Nations, if you like, and that they would put administrations in place to help endow these countries with constitutions and parliaments and executives and judiciaries, give them a good army to defend their frontiers, and when they’re up and running as viable states, then these benevolent mandates or mandatory powers would withdraw to allow these states to enjoy the free practice of government with full sovereignty.

Borders of the British Mandate of Palestine after World War I. (Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Now the Arab peoples looked at the way the Austro-Hungarian Empire was carved up, and suddenly new states like Czechoslovakia or Serbia or Yugoslavia were created, and said, there’s a double standard work here. Those people are no better prepared for ruling themselves than we are. But as it were, the territories of the Habsburg Empire had never been the subject of a wartime partition diplomacy. Those of the Ottoman Empire had been. And Britain and France were looking for their return on their war effort, and they would take satisfaction in Ottoman lands.

That gives rise to the partition that will give the international community a Syria, an Iraq, a Lebanon, a Palestine, a Jordan, all enduring legacies of that partition diplomacy, but the unresolved agendas that lay behind their creation, the frustrations of the indigenous people’s own wishes has given us a Middle East that has been a zone of conflict from their day to ours.

Chris Hedges: And of course, oil. I mean, you know, by the end of the First World War, Churchill, in particular, they realize that oil is… that’s how he forms Iraq, to make sure he gets all the oil fields. The Austro-Hungarian Empire didn’t have oil.

Eugene Rogan: No, no, neither did the French, for that matter. So you know the the idea that you would seize territory to gain access to a strategic asset like oil, particularly coming out of World War I.

Remember, they galloped into battle on horseback in 1914, they drove out in trucks and tanks and air [inaudible] the battlefield. It was a hydrocarbon society by 1918-1920. Oil was going to determine who would be an autonomous power and who would be a dependent country.

And so for Britain, getting, you know, access to the oil fields in the northern Iraqi province of Basra becomes a real war ambition again, Britain’s ever evolving ambitions on territory. The Brits fight ten or 11 days after the signing of the armistice with the Ottoman Empire to make sure they’ve secured Mosul before they put their guns to rest. So you know, oil is a huge part of that story, but interestingly, very much focused on Iraq. The British had no sense that there would be oil in Saudi Arabia, and they never even bothered there. But Iraq for sure.

Chris Hedges: At the end of the book, you draw parallels, you write the war on terrorism after the 11th of September demonstrated Western policy makers continue to view jihad in terms reminiscent of the war planners from 1914 to 1918. And so many of the mistakes that the British made, I mean the fall of Kut to go back, you know, has echoes of the American or the American occupation of Iraq echoes so much the British disasters and places like Kut but you do draw these parallels in your conclusion.

And just to conclude this interview, I’d like you to essentially speak a little bit about the modern Middle East and how what you wrote about informs what’s happening today.

Eugene Rogan: Well, I’ve always felt that one of the things that draws general readers to history is to try and come to grips with where we are today. My motto has always been, if you want to understand the mess we’re in today, you’re going to need some history. I would say that I teach history, right?

This is a professional interest, but I was just very struck by the ways in which this whole notion of jihad kind of inflamed European war planners, the Germans thinking this was their secret weapon, and instead of it really playing on Muslim sensibilities in Asia and Africa, the people who seem most susceptible to the call for jihad were actually British war planners.

They kept getting drawn deeper and deeper into the Middle East, fearing that every time the Ottomans beat them, that was going to be an incentive for the global jihad that was going to undermine their position in India, you know, having 80 million Muslims rise up against the white men in India would have been the end of empire.

And so they were very responsive to this. And I don’t mean to say that there was no reaction from the Muslim world. There was an uprising in Singapore shortly after the declaration of jihad, and for a week, Britain struggled to regain control over Singapore. So we know that this call could resonate to disgruntled Muslims who, confronted with imperial powers, decided to take the opportunity to rise up.

But the thing that was really striking to me was that there never was the mass uprising in support of the Sultan’s call for jihad. And why is that? Well, because Muslims in India or in the Caucasus or in North Africa have the same reactions to wars as you and I would, Chris.

You’re not going to immediately jump up and grab a sword because some guy 3,000 miles away or 5,000 miles away is trying to make you fanatical. They’re going to be most concerned about their daily bread, their children’s welfare, the pragmatic stuff that drives the desperate struggle for life.

That was what most people in Asia and Africa knew before 1914 and still know today and when I look to the war on terror, the reaction of the United States and its allies to horrific events like the 9/11 attacks was to assume that they were facing a global jihadist enemy and that Muslims everywhere were going to respond to the appeal of Osama bin Laden for having made this violent strike against the United States. But the fact of the matter is, it never happened.

And even if you take the most extreme example of jihadist thinking in the 21st century, the creation of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, you know, it was a marginal movement that was able to attract a lot of marginal Muslims from China, from Britain, from Belgium, from the United States, but in no way represented a kind of global uprising by the world’s ummah.

Most Muslims viewed the events of 9/11 with horror, and the aftermath of 9/11 sought to distance themselves from the extremists who perpetrated it. They felt themselves citizens of the countries they lived in. They felt themselves a target of anger, and they were angry at those who had put them in that position.

The idea of like the fanaticism driving Muslims to take collective action against their infidel enemies is one of those recurring wrong ideas that too often, our governments or our war planners have been persuaded of or persuaded ourselves.

So I was hoping in some way to try and just make readers question that call to fighting against the global jihad. I mean fight against violence, fight against violent organizations, absolutely. But to assume that all Muslims are going to respond in a collectively irrational way is, I think, one of the mistakes that was made 100 years ago in World War I, and still gets made today.

Chris Hedges: I just want to second that. I was in the Middle East for The New York Times after 9/11 and most Muslims, as you know, were appalled at the attacks of 9/11 and the tragedy is, of course, the way you fight terrorism is to isolate terrorists within their own society. And we responded just the way Osama bin Laden wanted us to respond, which was dropping iron fragmentation bombs all over Afghanistan, Iraq and eventually Syria and Libya and everywhere else.

And the other thing that I found kind of, you know, from your book, the other thing that was struck me was the idea that an occupying force, I’m thinking of General Maude going into Baghdad, occupying Baghdad and posting a proclamation that the British had come as liberators. There’s also this kind of fallacy.

We did exactly the same thing when, as from the United States, when we invaded back… I just found so many echoes grounded in a misunderstanding of the society, the culture and the religion that they were trying to dominate with the same kind of disastrous results.

Eugene Rogan: Yeah, I think that those proclamations of liberation people see through so quickly, and they’re not fools. You know when you’ve just been conquered and occupied and goodwill is always to be hoped for. But the idea that people invade your country for your interest rather than their own, is just a hard sell to recently occupied people.

Chris Hedges: Well, they saw through the British and they saw through us pretty quickly. That was great. That was Professor Eugene Rogan on his book The Fall of the Ottomans. I want to thank Sophia [Menemenlis], Diego [Ramos] Thomas [Hedges] and Max [Jones], the production team. You can find me at ChrisHedges.Substack.com.

Chris Hedges is a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist who was a foreign correspondent for 15 years for The New York Times, where he served as the Middle East bureau chief and Balkan bureau chief for the paper. He previously worked overseas for The Dallas Morning News, The Christian Science Monitor and NPR. He is the host of show “The Chris Hedges Report.”

The Consortium