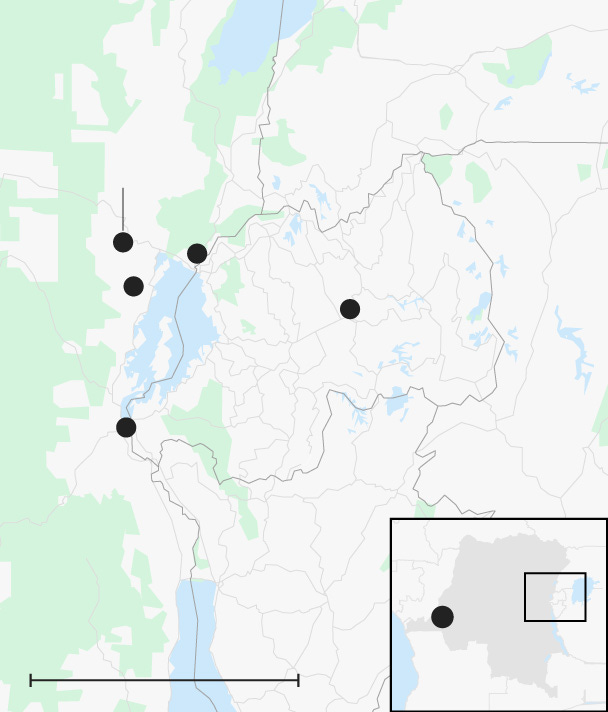

Hunt for tech-industry minerals reignites conflict in central Africa

Rwanda-backed M23 rebels seized Rubaya coltan mines before fighting displaced half a million people.

People dig in the Rubaya’s coltan mines using basic equipment of shovels and prospecting pans as was the case during the 19th century gold rush Credit: Simon Townsley

The hunt for tech-industry minerals in eastern Congo harks from a different age to the products they will become.

Filthy miners use only shovels and prospecting pans while scouring muddy hills for ores that will go into the latest smartphones and laptops.

In scenes reminiscent of the 19th century gold rush, these prospectors unearth 21st century treasures that keep the modern world running.

The mining town of Rubaya in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) even has the feel of the Wild West, complete with occasional gunfire from disputes over claims.

Nine months before the Rwanda-backed M23 rebel group last week seized the city of Goma, its fighters seized Rubaya’s coltan mines. The dull, black metallic ore is refined to tantalum, a heat-resistant powder used in capacitors for high tech devices.

The mines are a cash cow. Since taking Rubaya, the group is estimated by the United Nations to have earned £650,000 a month by imposing taxes on the coltan trade.

At the same time, each month 150 tonnes of coltan is smuggled over the border to be sold by Rwanda.

Workers scour the mud for ores that will go in the latest smartphones Credit: Simon Townsley

The capture of Goma now gives the M23 group and its Rwandan sponsors even greater control over an area rich in not only coltan, but also tungsten and gold. Deeper in DRC are huge deposits of cobalt, tin and copper.

The M23 capture of Goma has worsened what was already one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises, in an area blighted by war for decades.

More than 500,000 people were displaced by the fighting in January alone, and the UN says at least 700 people were killed in the fight for Goma in the past week, with 2,800 wounded.

The Red Cross said one of its hospitals had received more than 100 patients with head and chest wounds over 24 hours.

The race for such minerals did not cause the wars which have ravaged eastern DRC since the 1990s, but their riches have since become a significant motivation for the dozens of armed groups.

Men travel to the coltan mines to work. The M23 rebel group is estimated to have earned £650,000 a month via taxes on the coltan trade Credit: Simon Townsley

Jason Stearns, a political scientist and Congo expert at Canada’s Simon Fraser University, said: “Today, minerals play an enormous role.

“They are the main way that most armed groups fund themselves. Because minerals are such a huge part of the economy, that is one of the main sources of revenue for armed groups.”

Their role has even led some Congolese to liken them to the harmful conflict diamond trade and call them “blood minerals”.

Rwanda’s motivations are more murky.

The country strongly denies being behind the M23 group, or being after its neighbour’s minerals.

Rwanda’s ambassador-at-large for the Great Lakes region, Vincent Karega, this week rejected the idea that M23 was trafficking Congolese minerals.

He said: “Do you think it’s possible to fight and still have time to mine natural resources and refine them?”

Yet minerals from eastern DRC are hugely important to Rwanda’s economy and have been smuggled over the border long before M23’s recent advances.

Mr Stearns said: “One of Rwanda’s largest exports in recent years has been minerals and much of that comes from the eastern DRC.

“Last year, Rwanda exported $1.1 billion (£883 million) in minerals, most of that was gold and most of that came – we can estimate – from eastern DRC.

“Minerals play a large role in motivating Rwanda. Rwanda has other aims as well, Rwanda has fought five wars now in eastern DRC, going back to 1996.

“In general they want to control this area for a variety of reasons, but yes, minerals are one of those reasons.”

Numbi, another mining area rich in gold, tourmaline and tin, tantalum and tungsten, is also under threat.

Corneille Nangaa, one of the political leaders of M23, said: “We want to go to Kinshasa, take power and lead the country.”

The chances of the rebels getting to the capital nearly 1,000 miles from Goma are thought to be slim, but their advance already poses a headache for Rwanda’s allies, including Britain.

The M23 rebel group is still advancing to mining towns and says it wants to lead the country Credit: Arlette Bashizi/Reuters

Mr Kagame’s impressive strides in building up his country and bringing growth and stability after the horrors of the genocide have long made Rwanda a darling of international development donors.

Large sums have poured in, even as opposition figures have been killed and elections have delivered him a suspiciously high 99 per cent of the vote. Mr Kagame and his government have strongly denied any involvement in the deaths and have said there has been no vote rigging.

The country has a sponsorship deal with Arsenal to display its Visit Rwanda tourism logo on shirt sleeves.

When M23 previously captured Goma in 2012, international pressure on Rwanda quickly forced a withdrawal. In a world distracted by Ukraine and the Middle East and with a more isolationist America, it is unclear whether similar pressure will be employed.

A man guards bags of coltan

A man guards bags of coltan, which is used in mobile phones, computers, vehicle electronincs and cameras Credit: Simon Townsley

David Lammy, the Foreign Secretary, this week warned Mr Kagame that £800 million of global annual aid to Rwanda could be at stake, including £32 million a year from London.

He said: “All of that is under threat when you attack your neighbours”.

“We cannot have countries challenging the territorial integrity of other countries.

“Just as we will not tolerate it in the continent of Europe, we cannot tolerate it wherever in the world it happens.”

Telegraph Media Group Holdings Limited