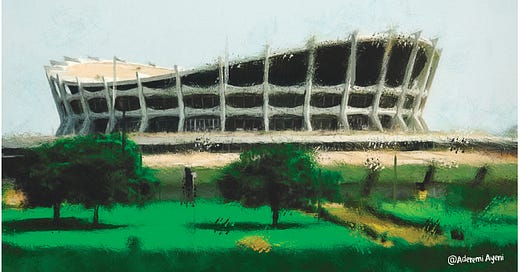

Nigeria’s national theatre: A cultural beacon at a crossroads

Duro Oni

The National Theatre in Lagos stands as a symbol of Nigeria’s artistic ambition, cultural pride, and national identity. Yet, its journey from grandeur to neglect mirrors the broader story of Nigeria itself – a nation of bold beginnings and unrealised potentials. Today, efforts to restore this iconic monument offer hope, but the question remains: will this revival be sustained, or will history repeat itself?

Conceived in the 1970s as a hub for artistic excellence, the National Theatre was designed to showcase Africa’s rich storytelling traditions and cultural heritage. Its construction began under General Yakubu Gowon’s military regime in 1973 and was completed by General Olusegun Obasanjo in 1976. Modelled after Bulgaria’s Palace of Culture and Sports, the theatre’s imposing modernist dome was equipped with state-of-the-art facilities, including a 5,000-seat auditorium, banquet halls, cinema halls, exhibition spaces, and an art gallery.

At its zenith, the National Theatre pulsed with life. It hosted FESTAC ’77 – a landmark festival celebrating Black and African arts and culture – with over 17,000 participants from across Africa and the diaspora. The theatre became a beacon for playwrights like Wole Soyinka and dramatists staging productions such as Camwood on the Leaves and Isiburu. It was not just a building; it was a declaration of Nigeria’s creative prowess to the world.

Despite its promising start, the theatre’s fortunes waned over time. By the late 1980s, economic downturns, shifting political priorities, and bureaucratic inertia led to chronic neglect. Routine maintenance was abandoned; leaking roofs, malfunctioning air conditioning systems, and structural decay became emblematic of broader mismanagement.

The military regimes that dominated much of Nigeria’s post-independence history had little interest in artistic expression beyond ceremonial performances for VIPs. Funding for the arts dwindled, forcing the theatre’s management to rent out spaces for weddings and church services just to stay afloat. As live theatre lost relevance to Nollywood and digital platforms, opportunities for performers diminished. Many sought creative prospects abroad, fuelling a brain drain that weakened Nigeria’s artistic ecosystem.

The ripple effects extended beyond artists. Cultural tourism stagnated as Nigeria failed to capitalise on its creative industries. Where Broadway in New York and London’s West End generate billions annually through cultural tourism, Nigeria’s National Theatre became a symbol of wasted potential – a husk of what could have been an economic powerhouse.

In July 2021, the Bankers’ Committee and Central Bank of Nigeria launched an ambitious N65 billion restoration project to revive the National Theatre as part of broader efforts to unlock Nigeria’s creative economy. By September 2024, renovations were nearing completion. The upgrades included refurbished auditoriums, exhibition halls, banquet spaces, improved landscaping, parking facilities, and enhanced security systems.

More significantly, four creative hubs – dedicated to fashion, music, film production, and information technology – were integrated into the 44-hectare site surrounding the main building. This transformation positions the theatre not just as a performance venue but as an incubator for innovation in Nigeria’s creative industries. With an estimated value now in the hundreds of billions of naira and the potential to create hundreds of thousands of jobs, the creative sector could become a cornerstone of economic diversification beyond oil dependency.

While physical restoration is promising, it alone cannot secure the theatre’s future. Sustainability demands more than infrastructure – it requires strategic policy frameworks that prioritise cultural investment as an economic imperative. Countries like India, South Korea and Brazil have successfully leveraged their arts industries for national branding and global recognition; Nigeria must do the same by integrating its creative sector into broader development strategies.

Diversified funding models are also essential for long-term viability. Successful cultural institutions worldwide thrive on balanced revenue streams from ticket sales, private partnerships, philanthropic support, grants, and endowments – not solely on government budgets prone to unpredictability or neglect. Public-private collaborations like those spearheaded by the Bankers’ Committee and the CBN offer hope but must be institutionalised for lasting impact.

The National Theatre remains a potent emblem of what is possible – a reminder that art is not a luxury but a necessity for national development. Its revival offers Nigeria an opportunity to reclaim its place as a cultural powerhouse by treating creativity as both heritage preservation and economic strategy

Will this restoration mark a turning point or another fleeting attempt at reviving nostalgia? The answer lies in sustained commitment – not just to restoring walls but to nurturing stories that inspire generations and elevate Nigeria on the global stage.

The fate of the National Theatre reflects our collective values as a nation: whether we choose to invest in our creative spirit or resign ourselves to indifference will determine if this monument rises again – not merely as a building but as the beating heart of Nigeria’s artistic.

Prof. Duro Oni, a former Deputy Vice-Chancellor of the University of Lagos, is an advocate for cultural economics and a former adviser on the creative industry.

BUSINESSDAY MEDIA LTD